September 30, 2022

Reinventing Cowtown

By Sarah Hepola, Texas Highways Magazine, October 2022

There’s never been a better time to visit Fort Worth.

Local entrepreneurs and large-scale development have kick-started a creative renaissance in Fort Worth.

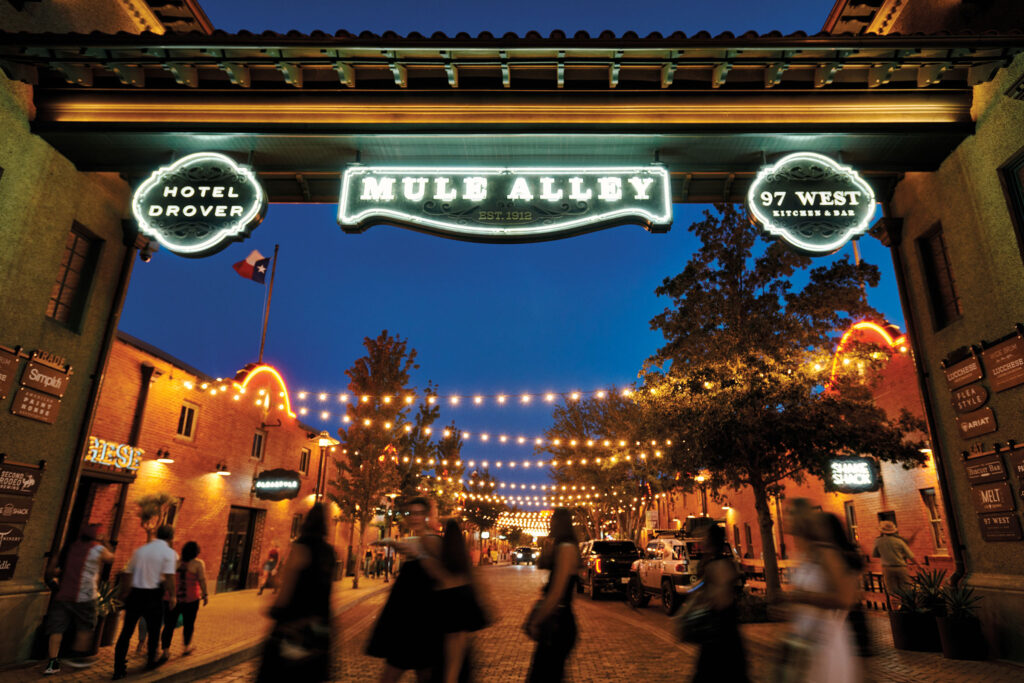

…Fort Worth is the 13th largest city in the country, but locals like to point out the place feels more like a small town. You can get to most places in 15 minutes. Folks are happy to chitchat. The laid-back vibe is a huge part of the appeal, but the downside has been that the place can feel a bit provincial. Over the past few years, a renaissance of development and creative energy has found the city stepping into its size. Some of this owes to innovative thinking by individuals like Ruth, and some traces to large-scale development efforts. The $540 million Dickies arena near the Stockyards has brought both Paul McCartney and professional bull riders to town. The $300 million Clearfork development carved out a piece of the enormous Edwards Ranch to build upscale shopping and alfresco dining along the Trinity River. On the other side of the Stockyards from Hookers Grill, visitors can find the $175 million renovation of Mule Alley, where a long-vacant stretch of horse and mule barns have been vibrantly reimagined as retail and dining.

Rising up at the end of Mule Alley is Hotel Drover, whose name pays homage to the cattle drovers who once rode the trail—a tradition kept by the Stockyard’s twice-daily cattle drives. Outside, a neon cowboy welcomes folks to a property that is chic enough for gawking but relaxed enough for hanging. “If there was a cattle baron’s estate in the Stockyards, this would be it,” says Craig Cavileer, managing partner for the Stockyards Heritage Development Co. On a Friday night, the high-ceilinged lobby bar is bustling with young couples, families gathered on leather couches, and clusters of women in wedge heels and cowboy boots sipping wide-brimmed cocktails. The Drover’s 1-acre backyard is a delightful ramble, with fire pits and live music and a gravel path that opens onto the Trinity Trail. Hotel Drover so nailed the upscale down-home aesthetic that Travel + Leisure readers recently voted it the best hotel in Dallas-Fort Worth.

But some of the exciting innovation has happened on a smaller scale. Take Inspiration Alley, where local artists transformed an ordinary back alley into a 4,600-square-foot immersion of murals that explodes with whimsy and color. Introduced in 2017 and expanded in 2021, Inspiration Alley is the heart of The Foundry district, developed by 30-something twin sisters Susan Gruppi and Jessica Miller, who started refurbishing the low-slung warehouses in 2015 and soon attracted eclectic businesses. Aruna Hanna opened her high-end saddle refurbishing store, Double Oak Tack, in The Foundry in 2021. “I like that it’s artsy and fun and caters to businesses that are super unique,” Hanna says. She relishes watching locals arrive to take selfies in front of Inspiration Alley, from women in wedding dresses, kids in graduation gowns, and, once, a person riding up on a horse.

…I grew up in Dallas, only 30 minutes from Fort Worth, and I can quickly summarize what I thought about Fort Worth in those years: I didn’t. About once a year, I loaded into someone’s SUV for field trips to the museums or the Stockyards, but the city had the feel of obligation to me. I’d grown accustomed to shopping malls and boxy skyscrapers, and I never felt comfortable around the pens of goats and pigs tended to by country kids who had the bad fortune not to live near a Gap. This was very Dallas of me. Although Dallas and Fort Worth have been roped together into the DFW metroplex, the country’s fourth-largest urban area, they have always been foils.

“People call them the twin cities, but it’s like twins standing back-to-back and looking opposite directions,” says Bud Kennedy, a longtime writer for the Fort Worth Star Telegram. “Dallas always looked to New York and London and Paris, and Fort Worth looks west to the prairie and the cattle ranches and the oil fields.”

Another way to say this is that Dallas distanced itself from its roots, while Fort Worth embraced theirs. Or, as the late sportswriter Dan Jenkins, who lived in Fort Worth, put it: “If you want to see Atlanta, go to Dallas. If you want to see Texas, go to Fort Worth.”

A military outpost in the mid-19th century, Fort Worth got cooking when the Texas and Pacific Railway came to town in 1876, and it became a stop on the Chisholm Trail. Cattle ranchers were the first millionaires, drawing meat-packing firms like Swift and Armour to the Stockyards in 1902, and turning Fort Worth into a blue-collar town during the decades when white-collar Dallas rose as a banking and retail center. Fort Worth newspaper magnate Amon Carter, born in a log cabin in the small North Texas town of Crafton, was apparently so disdainful of Dallas snobbery that he brought a sack lunch to business meetings so he wouldn’t have to give the city any money.

Carter was the man responsible for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and he also popularized the city motto “Where the West Begins.” He’s one of the philanthropists whose values—and fine art collection—shaped the town. When Dallas was chosen for the Texas Centennial in 1936, Carter didn’t like the idea of Fort Worth being upstaged, so he secured funding for the Will Rogers Memorial Center. In 1944, it became home to the stock show. A museum bearing Carter’s name, housing Western art, opened in 1961 in the emerging cultural district, which grew to include the Museum of Science and History, the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, and the elegant grounds of the Modern Art Museum.

The 1972 opening of the Kimbell Art Museum put Fort Worth on the cultural map. Kay Kimbell owned more than 70 businesses, from grain to oil, but he and his wife, Velma, had amassed a collection of works by old masters, including Michelangelo and El Greco. After Kay died, Velma commissioned architect Louis Kahn to build a museum that would become a high-water mark in modernist architecture. A series of austere barrel vaults, made of concrete, travertine, and white oak, the Kimbell is striking from the outside but a marvel of light on the inside, with skylights that run along the ceiling like a silvery spine. Its permanent collection includes Asian and African art, but the bigger draw is European art that time travels from Caravaggio to Monet to Picasso. The museum elevated the city’s reputation by providing a highbrow mecca in a prairie town, a curious intersection of cows and culture. The museum will mark its 50th year in October. “I’m delighted to celebrate this enormous milestone with our Fort Worth community,” museum director Eric M. Lee says. A week of events kicks off Oct. 4 and includes architecture tours and a family festival on Oct. 8, in addition to a yearlong exhibit on the museum’s history, The Kimbell at 50.

The ’80s saw the rise of Sundance Square, an urban revitalization before such a term was coined. The project was the brainchild of the Bass family, four billionaire brothers whose wealth began with $2.8 million inheritances from their oil tycoon uncle Sid Richardson, another Fort Worth patron. Suburban flight had emptied downtowns across the country, and in 1979, the Bass brothers began quietly acquiring those derelict properties and restoring them to hotels and retail and restaurants, inspired by urbanist Jane Jacobs, a champion of mixed-use development and historic preservation. They named the area after the gunslinger the Sundance Kid. As the area grew into a thriving entertainment district, including the 1998 opening of the $67 million Bass Performance Hall—a glorious concert venue whose development was led by brother Ed Bass—Sundance Square became a blueprint for downtown renewal across the country. More recently, it paved the way for revitalization efforts in once-blighted areas of Fort Worth like Magnolia Avenue and the Near Southside, which have become two of the city’s trendiest neighborhoods.

All this turned out to be quite the draw. For many of the past 20 years, Fort Worth has been the fastest growing large city in the country. It’s also the youngest large city in Texas, edging out youthful Austin (33.7) with an average age of 33. This may be partially due to Fort Worth’s growing Latino population, which was about 35% in the 2020 census, up from 19% in 1990. Families flocked to a part of the state that offered affordability and opportunity. With its sleepy vibe and lack of pretentiousness, Fort Worth started to look something like the lost dream of old Austin, which is not necessarily something the locals like to hear. “We saw what happened to Austin,” Kennedy tells me.

These days Fort Worth real estate is not much cheaper than Dallas. “I can’t think of a neighborhood that isn’t hot right now,” says real estate agent Lisa Logan. Logan has worked in real estate for eight years and has seen a large portion of the city’s homes nearly double in price from where they were 15 years ago. “People want a place where houses are cheap, and the people are cool,” she sighs, as if watching that ship sail. “Maybe two and a half years ago, but not now.”